It’s been two and a half years since I went to Mexico to start studying the globalization of milk consumption and this blog. My intention was to update it frequently but as soon as I returned to the US, I jumped into so much activity that writing this milk series took a back seat. Nonetheless, I did produce some posts here and on the Seed the Commons blog. I’ve also built awareness by speaking about the globalization of dairy at numerous venues, and I spearheaded the Seed the Commons campaign to #GetMilkOut of San Francisco school meals, which was launched on September 30, 2017. I am resuming the milk series with the hope of updating it more frequently, perhaps with shorter posts. For this one, I want to take a step back and speak about why I chose Mexico as my focal point.

I started this project to study a convergence of issues related to the globalization of dairy, including: the role of food aid in creating new markets for donors and integrating local food systems into a global capitalist market; the soft power of the West and the power of dominant groups to define what is normative; the social representations of non-European cultures, bodies, and ultimately of poverty, that justify a non-profit/development/humanitarian complex that furthers neocolonialism.

The first iteration of this project was a PhD I started in 2009, and I got the idea for it while I was working in the world of international human rights in 2007. I already knew that I wanted to explore the role played by the “non-profit industrial complex” and international institutions in maintaining a neocolonial world order, and I had an interest in food aid because I considered the usurpation of food systems central to this order. The idea to study milk distribution came about when I read an article about a joint program between Kraft and Save the Children: a school milk program in Mexico.

I read more about school milk programs, realizing how widespread they were becoming and how instrumental they were in changing food cultures around the world. The project crystallized and I decided to stick with Mexico for a number of reasons.

Poster Child for Neoliberalism and American Influence

The westernization of food cultures in the Global South, namely the increased consumption of animal products and processed foods, is largely the result of neoliberal policies and in this Mexico is a perfect case study. As the country that has ratified the largest number of free trade agreements, Mexico seemed like a poster child for the effects of free trade. The effects of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) on Mexican food systems are particularly well documented and are often spoken about in activist circles to illustrate the damage wrought by free trade agreements in the Global South.

That NAFTA involves the Unites States is also important, as Mexico’s close relationship with the United States is another area where it provides a magnified view of the direction the rest of the world is taking. “Westernization” often amounts to Americanization, and from food culture to economic policy, much of the world takes its lead from the US. NAFTA has been a boon for the American dairy industry, for which Mexico is the largest export market. Mexico not only has important economic and political ties with the US, but also a very close cultural proximity.

The history of milk distribution in Mexico is also linked to its relationships with other parts of the Global North. Dairy was introduced to Mexico by Spanish colonizers and its consumption started to rise significantly in first half of the 20th century. At this time, Nestlé opened the first dairy processing plant in Mexico and this Swiss company subsequently became involved in both the Mexican social sector and in the technical development of its livestock industry. Also during this time, the first milk distribution programs created new outlets for foreign dairy industries.

Layers of Cultural Imperialism

As Mexican diets and diseases become stereotypically American, the influence that the United States exerts onto its southern neighbor provides a great case study of the power of a dominant group to define dietary norms. However, dairy is not an altogether recent food in Mexico. The increase in dairy consumption over the course of centuries reveals other layers of cultural influence that are rooted in Mexico’s history of colonization. The story goes that the Spanish conquered Mexico and a culinary fusion of indigenous and Spanish foods gave rise to what we know today as Mexican food, but it would be more appropriate to view the adoption of Spanish foods as a gradual process. Some indigenous communities still eat predominantly indigenous foods and their adoption of Mexican (in the sense of modern-day Mestizo) food culture is a current, ongoing process.

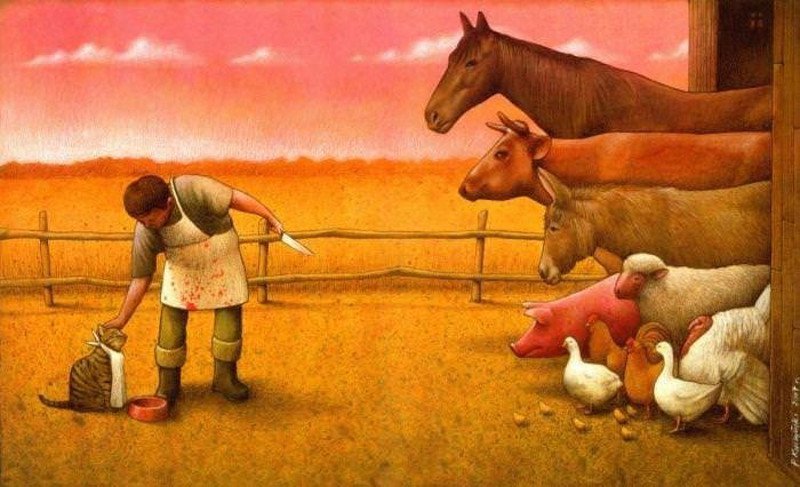

Among my criteria for choosing a country were that milk would not be a traditional food and that a high percentage of the population would be lactose intolerant. Indigenous Mexicans fit the bill. And since the goal was to examine at the social dynamics by which a dominant group shapes the dietary norms of a subordinate group, the evolving and overlapping relationships of power between indigenous Mexicans and Europeans, Mexicans and Americans, and indigenous Mexicans with Mestizo culture make Mexico a very rich terrain.

The issue of lactose intolerance was important because it brings into salience the power dynamic between those receiving new foods and those promoting them (especially when these are authority figures such as doctors, nurses, aid workers, and teachers). While lactose intolerance is not as high in Mexico as in some other countries where milk consumption is being adopted as a new norm, it does play into the changes underway, as both indigenous and Mestizo populations produce strategies to deal with their impediment in consuming a food that they are told is necessary.

One-Eighty: from Plant-Based to Carnism Extraordinaire

Common representations of Mexican food are heavy with meat and cheese, but pre-Columbian Mexican food was almost entirely plant-based. Today, while consumption levels of meat and dairy remain lower in Mexico than in wealthy countries, they are quite elevated by Global South standards and are highly appreciated and culturally valued. As I set out to explore the social mechanisms of dietary change, I found Mexico fascinating because it presented the widest possible change.

There are many countries and populations where milk consumption has skyrocketed from next to nothing. However, in many of them animal domestication and/or the consumption of animal products had a longer history or were more culturally significant. The story of Mexico illustrates the true malleability of culture and even of social identity, and how these are shaped from above by those who dominate socially, politically and economically.

At the same time, the story of food in Mexico also shows us strategies of resistance. From Zapatistas replanting milpas on reclaimed lands to massive popular mobilizations against Monsanto and indigenous women selling donated milk in the market, Mexico is full of examples of people exerting the right to protect and determine their own food systems and culture. While milk is dumped onto communities around the world, the processes by which it is adopted or rejected can be quite complex. Mexico is the perfect place to unfold it all.